The Domestic Soundscape making, listening, thinkingfelicityford@outlook.com

A Feminist Approach to the Domestic Soundscape

Here is a transcript of the Paper I gave at this year’s Conference: A Woman’s Place, organised at Newcastle University earlier this year by Lucy Gallagher and Emma Short.

I’m doing a practise-based PhD at Oxford Brookes, where I’m looking at the domestic soundscape and the use of everyday sounds within arts practise. I’m going to start today by talking about some of the ideas I’ve inherited from earlier feminist art that deals with domesticity, then I’m going to discuss a piece of work that I made which attempted to synthesise some of these ideas. I then want to briefly cover the idea of subversion as a way of creating meaning, and then finish up with looking at the more celebratory approach that I’m now interested in adopting.

My practise is particularly informed by the area within feminist art-making that addresses undervalued and neglected areas of human experience. There’s a great trend towards the end of the 1960s and throughout the 1970s, towards making work that specifically attempts to dismantle the established borders between Art and Life. So I’m talking about feminist artists who insistently demand that we see more representation of things like housework, and that we see more instances of Art and Life intervening.

Let’s start by looking at the Maintenance Art Manifesto, which was written in 1969 by Mierle Laderman Ukeles. The full title of this work is ‘Maintenance Art-Proposal for an Exhibition.’ Ukeles wrote this manifesto after becoming pregnant and looking critically at the perceived split between her labour as a mother and housewife, and her labour as an artist. The Manifesto proposes an exhibition in which the artist lives and perform the tasks associated with maintenance and living, as the actual art work. I’m going to read some of the manifesto to you, and put this image up:

This is Mierle Laderman Ukeles undertaking domestic chores at the Hartford Art Museum in a 1973 performance. In the performance, she washed the floor of the museum during regular public visiting hours.

This is an extract from her Manifesto:

I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife. I am a mother.

I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supportive, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I “do” Art.

Now I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art. I will live in the museum as I customarily do at home with my husband and my baby, for the duration of the exhibition, and do all these things as public Art activities: I will sweep and wax the floors, dust everything, wash the walls, cook, invite people to eat, etc.

MY WORKING WILL BE THE WORK.

In this manifesto and in this work, Ukeles demands both that we question the values we confer on Art and the values we confer on housework. The means by which this work operates are entirely subversive, exposing the mechanisms by which we assign values to either Art or Housework. The work demands that the artist must be allowed to synthesise her two realms of labour into one, which is an idea that is especially interesting to me, and to which I will later return in this talk.

Another art project that is essential to mention here is the Womanhouse project, which began in 1971 when 21 art-students, led by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, took on the idea of physically creating an exhibition in a house. Unlike Ukeles work, which relates specifically to service and labour, Womanhouse was a project that was really about women’s imaginative engagement with the house or the home as a kind of feminine environment… Judy Chicago writes in her book, ‘Through the flower, My struggle as a woman artist,’

Women had been embedded in houses for centuries and had quilted, sewed, baked, cooked, decorated, and nested their creative energies away. What would happen, we wondered, if women took those very same homemaking activities and carried them to fantasy proportions?

…Room after room took shape until the house became a total environment, a repository of female experience, and womanly dreams….

Womanhouse provided a context for work that both in technique and in content revealed feminine experience. There were quilts and curtains, sewn sculptures, bread-dough pieces, and a crocheted room, Womanhouse became both an environment that housed the work of women artists working out of their own experiences, and the “house†of female reality into which one entered to experience the real facts of women’s lives, feelings and concerns.

In one sense, Womanhouse can be read as a kind of consolidation of stereotypes surrounding femininity. You have all these materials and ideas which relate to traditional ideas about what women do, what women think about, and, crucially, where women belong. And an easy criticism to make is that Womanhouse confirms certain ideas about women and domestic space. On the other hand, I think it is historically a very important work from the point of view that it really is a project in which women author their own experiences of the home, rather than being in some way subject to the home; this idea of authorship is very important to my own practise.

Looking at this idea of authorship, let’s take one example from Womanhouse in which the woman is the author of the piece; in this instance a performance piece entitled ‘Waiting’ and an example of a Victorian genre painting of the same subject; we’re going to look at Ford Madox Brown’s painting, ‘waiting.’

In the image by Ford Madox Brown we see the artist interpreting and describing his ideas about the woman. The woman is the subject of the painting; not the author. In this painting the woman featured ‘waiting’ was in fact modelled on Madox Brown’s wife and the child in her lap is his daughter. The woman is waiting for her husband to return from the Crimean war; the depiction of her domestic moment has been appropriated for this topical reference and is arguably not the full point of the painting. Described by various critics as a painting with ‘a quiet intensity,’ Ford Madox Brown’s ‘Waiting’ has been compared to images of the Madonna and child and we see the familiar, sentimentalised and idealised vision of domesticity that was so popular in the Victorian era. The woman in the painting is mute, ideal, quiet and industrious. Her waiting is virtuous and it is done in relation to her husband. His absence is the focus of her actions, she is realised in relation to him and her child. But there is nothing in the painting that suggests things ought to be otherwise. This is, in fact, the correct way for her to behave as far as Victorian society dictates.

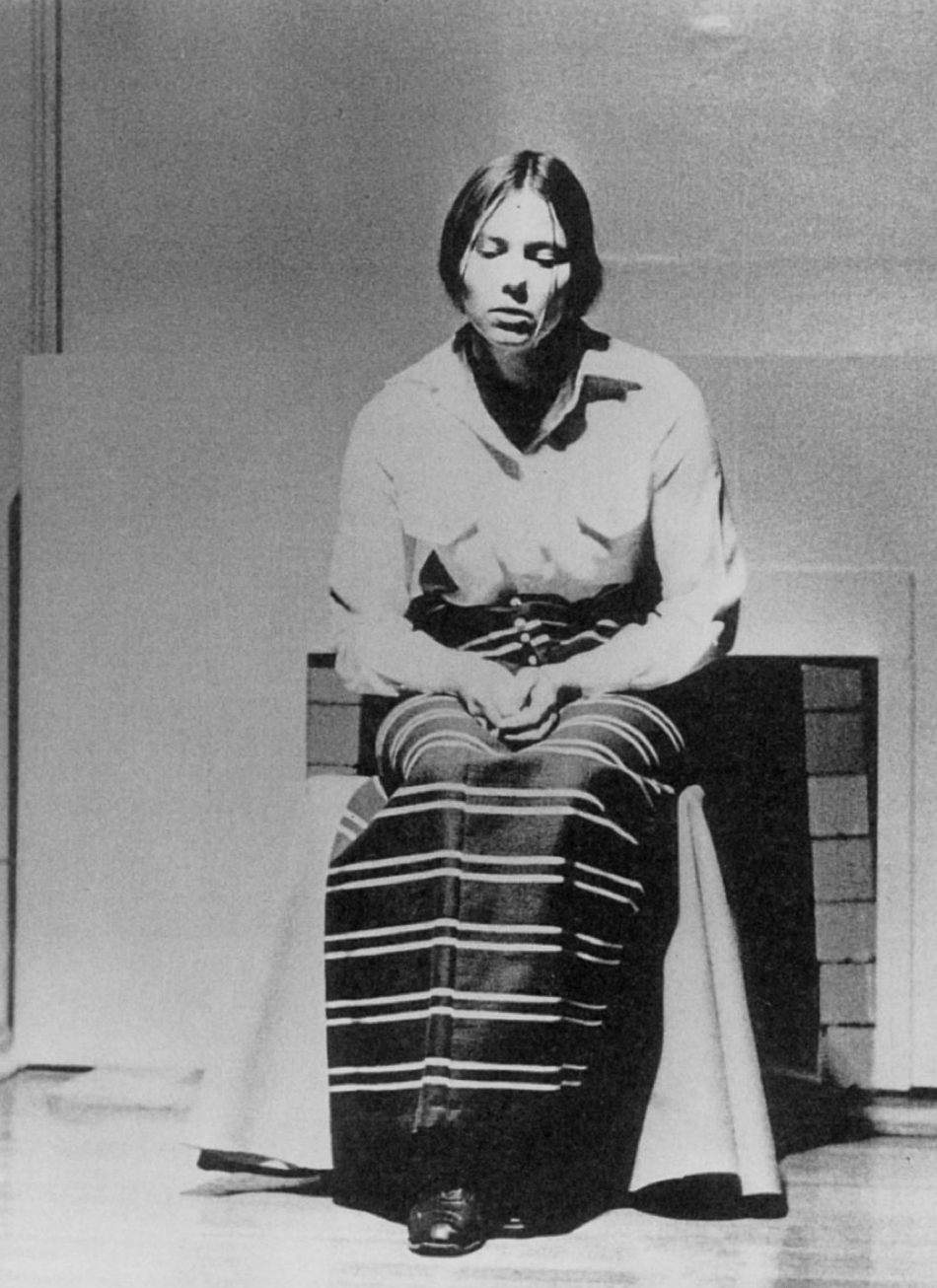

Contrastingly, Faith Wilding’s behaviour in Waiting is somehow ‘incorrect;’ hers is not a performance intended to maintain the status quo; rather it is a challenge to, and a lamenting of, woman’s reliance on others.

Here is an excerpt from the poem she performs as part of ‘waiting,’ the performance documented in the photograph here:

Waiting for my children to come home from school

Waiting for them to grow up, to leave home

Waiting to be myself

Waiting for excitement

Waiting for him to tell me something interesting, to ask me how I feel

Waiting for him to stop being crabby, reach for my hand, kiss me good morning

Waiting for fulfillment

Waiting for the children to marry

Waiting for something to happen Waiting . . .

Waiting to lose weight

Waiting for the first gray hair

Waiting for menopause

Waiting to grow wise

Waiting . . .

Waiting for my body to break down, to get ugly

Waiting for my flesh to sag

Waiting for my breasts to shrivel up

Waiting for a visit from my children, for letters

Waiting for my friends to die

Waiting for my husband to die Waiting . . .

Waiting to get sick

Waiting for things to get better

Waiting for winter to end

Waiting for the mirror to tell me that I’m old

Waiting for a good bowel movement

Waiting for the pain to go away

Waiting for the struggle to end

Waiting for release

Waiting for morning

Waiting for the end of the day

Waiting for sleep Waiting . . .

I read Wilding’s performance ‘Waiting’ performed in Womanhouse in the 1970s as a revision and correction of the silence of waiting women in previous period’s of art’s history. Most un-Madonna-like and most unquiet, Wilding lists the waiting a woman does in her girlhood, in her adulthood and in her senior years in a stark and depressing poem.

We are embarrassed by the reflection she offers us, of woman’s disempowerment. I believe Wilding offers us her lament as a provocative gesture; one intended to leave us galvanised and more self-aware. Although she – as Madox Brown’s domesticated subject – sits in a chair, in a house, in a long dress, it is her own version of this situation that we hear and we are commanded, by her poem, to perceive the relationship between this image of the woman sitting at home and the related disempowerment and reliance on others that are itemised so powerfully in her poem.

This is not a man’s version of a wife’s dutiful waiting, this is a woman’s articulation of what it means to feel one’s life has not yet started.

Although the words seem damning, although the image painted before us by the words and the performing figure seem somehow to be affirming the pitiable nature of women, I believe the artist in the performance of Waiting, is actually a very powerful and active figure. In authoring the experience of waiting herself, Faith Wilding is able to expose the noxiousness of the waiting; its threat to the life-force of the woman who is doing the waiting. The use of disempowered phrases in the poem is subversive; in each line that says what Wilding is waiting for, resides the implicit message that she could choose not to wait for others, but to do instead for herself.

Her poem is also a sad lament of the tragedy of life lived exclusively in relation to others; it is also an empowered gesture; one specifically connected to the artists’ ego.

One of things that strikes me about this issue of authorship, is its relationship to empowerment, and to that of the artists’ ego. In her immensely important book, The Obstacle Race, Germaine Greer talks about how it is because we live in relation to others and therefore have constantly to choose between being a woman (living in relation to others) or being an artist (living in relation to the self) that history has thrown up ‘no female Titian, no female Poussin,’ etc. is ‘that you simply cannot make great artists out of egos that have been damaged.’ She writes that

,The choices are before her: to deny her sex, and become an honorary man, which is an immensely costly proceeding in terms of psychic energy, or to accept her sex and with it second place, as the artist’s consort,To live alone without emotional support is difficult and wearing and few artists have been able to survive it. For all artists the problem is one of finding one’s own authenticity, of speaking in a language or imagery that is essentially ones own, but if one’s self-image is dictated by one’s relation to others and all one’s activities are other-directed, it is simply not possible to find one’s own voice.’

This sentiment is very much echoed by another important influence for me, Bobby Baker, who also felt keenly the impossible choice between womanhood and artist as vocation, but eventually found her own language through performance and foodstuffs.

Bobby Baker felt, all the time at Saint Martins, an anxiety that someone would tap her on the shoulder and say, ‘you can’t be an artist, you are a woman.’ She made a cake, carved a boot from it, decorated it with icing, and looked at it. The revelation that she then describes, ‘the new thought’ that shone, was that this cake was no more a cake, it was a sculpture. It was a work of art just as Anthony Caro’s huge sculptures were.

Bobby Baker writes of this realisation;

I had discovered my own language, material, form…

Bobby Baker made the Baseball Boot cake that precipitated this revelation, in 1972. These are the artists that have inspired me to find my own material, my own form. For me, the material I want to use, is the sound that constantly surrounds me in the home, where I have spent a huge amount of time – partly due to disability (I got arthritis when I was 19) and partly due to my fascination with and genuine love of, domestic space.

My use of domestic sounds goes back to a piece I made in 2004 for my graduate degree show.

I’ll play that to you now.

Apart from obviously being about body-image and weight issues, and containing a degree of triumph over my former bullies, this was the first work I made directly about my own experience, rather than trying to make something more abstract or cerebral. Like Wilding’s performance ‘Waiting’ the process of documenting and articulating my own account of body-image issues in my own language and using my own images, was immensely empowering. The most important thing to note about Whale is the enormous effect that creating the soundscape had on me. I lived very close to the sea at the time when I made the recording, but I chose to recreate the sounds of the ocean by lying in the bath and making all the sounds that way. I deliberately wanted to use sounds as a kind of material, for me, the associations with the bathwater rather than the sea, gave the recording a kind of intense intimacy and also a sense of re-creating a memory rather than illustrating the memory. To actually record the sea would have been, for me, a very literal translation of the idea of the piece and also a mere illustration or sonic decoration of the story. I wanted to use sound very much as a material in itself, to take the qualities and associations of a domestic space – the bathroom – into this story. To contextualise it, really. And it’s interesting how even when I listen to the piece now, I recall the bathroom which is really the area – with its mirrors and necessary nakedness – where body-image issues are most keenly experienced.

So this is the first example in my own work of where you see evidence of these other influences. I’m interested in making work that uses my personal voice as its main means of communication, that takes the actual sounds I experience in my daily life and uses them as a kind of fabric and that attends to issues or areas of life normally considered to be unworthy of artistic attention.

Now the other side of my feminist approach to the domestic soundscape concerns the position of my practise in relation to the field of phonography, experimental sound-art etc. So this world of experimental music. Which is implicitly gendered as a masculine or male-dominated environment. If cakes and knitting and crocheting and waiting and making bread are implicitly feminine, then mixing desks, screwdrivers, mini-jack leads, soldering irons and the maplins catalogue, are implicitly masculine.

So I made this work that was really about synthesising the worlds of constructed masculinity and femininity and it didn’t really work, but I’ll show you it now, and we can talk a bit about why it didn’t work.

This is the knitted speaker sound-system. My idea here was to somehow synchronise the means of presenting sounds, with the sounds themselves. Rather than providing the standard, black and chrome speaker system associated with sound-work, I wanted to somehow present the sounds via a listening system that was in tactile and visual appearance, more inexorably linked to domesticity. The soundscape I played through these speakers was comprised of many domestic sound-textures. I had taken the sounds of rice boiling, rain falling, tea being made, television humming in the background etc. and ‘woven them’ into a kind of soundscape. (You can also hear this at the bottom of this post.)

Unlike with the visual arts, there is little precedent for sound work that specifically deals with domestic space, from a feminist perspective. This work was incredibly awkward and confusing for my audience. There was a lot of disappointment that all the speakers seemed to be playing the same sound; the dispersion of the sounds into space, like a kind of sonic texture, was not really of interest to anyone except me, and the relationship between the knitted soundsystem and the sounds playing through the sound-system was baffling to many.

At the time, this was how I evaluated the work;

All the recordings used in the final composition came from specific moments where I was living in my house and contemplating the meaning of my actions. The desire to preserve and relate the very ordinariness and banality of those sounds as they happened in real time was what prompted the decision to create an appropriate sound-system.

I hoped the knitted speakers would comprise an appropriate sound-system; that they would provide a warm and intimate invitation into the sounds themselves, and reference domestic industry. I wanted it to be possible for the audience to experience the sounds at very close quarters and to fully immerse their listening in those sounds because domesticity is real for everyone. I intended the space at a distance from the work to be filled with a general wash of domestic sound-textures; rain falling on the roof of a parked car, things bubbling in a saucepan, an electric kettle boiling combined into a kind of soup etc., and for this wash to take people to their own sonic memories and moments of home.

As it was, the configuration of the speakers was confusing for the audience:

Feedback I got was that that people were puzzled by the jarring contrast between the angular sounds playing and the woolly softness of the speakers; that the correspondence between what you hear and what you see doesn’t make sense; that the suspended-speaker-structure looked welcoming and positive but that the sounds playing within it were detailed and required concentrated and effortful listening, and so on. In retrospect I feel the knitted speakers and the domestic sounds are a somewhat clumsy and literal combination of elements that didn’t really convey what I was meaning them to convey. The speakers didn’t reverently frame the sounds in a way that inspired people to hear everyday sounds differently. Something in my decision-making process overcomplicated the audience’s experience and made the work difficult to understand and the connection between the knitted speakers and the domestic sounds was not the readily identifiable link I had supposed it would be.

In the write-up, I then speculated about how using my own voice in the work may have clarified the work for the audience and looked at the score which I had originally developed. I concluded my criticisms of this work by saying:

Introducing such statements as ‘maybe it’s the girl in me’ into the sonic textures of this work would lead people to entirely different conclusions about its meaning. Sensuality, gender and domesticity would maybe become more evident, along with exaggerating the private/public threshold within the work. It is difficult to speculate at this stage, but I think in many ways this would comprise a more risk-taking and vulnerable work than the unexplained collage of field-recordings that existed in the first incarnation of Listening with Care.

The need to resolve the issue of form and content within this piece motivated my decision to apply for funding to research the territory of the domestic soundscape, and in this, I am looking very much towards making work which succeeds in celebrating and exposing the value of everyday sounds.

One of my core intentions or aims is to reconcile my role as a woman and my role as an artist into one thing so that the my experience of being in the home is always authored and informed by my contemplation of that space from the point of view of being an artist. Like Faith Wilding, I want to author my experiences of being in the home and to articulate them to a broad audience. I find it very empowering to record the world around me and to document all the sounds which are generally considered to be boring and meaningless. I also find that recording sounds is an amazing way of physically recreating the space and moments in time that exist within the home – because sound physically describes space and time in a way that photos or static images simply cannot – and that my relationship to the home as a recordist, investigator and commentator makes my relationship to domestic space an empowered and questioning one. Like Bobby Baker I am interested in finding a way of using the material that comes readily to me – sound – as a way of articulating my personal experiences. Like Mierle Ukeles I am interested in bringing materials from the home and my life in it, into the public realm of the art exhibition, because I still believe the home and the work that is still largely done by women in the home, to be undervalued. I find the contact that recording sounds necessitates between myself and unfamiliar technologies very empowering in itself, having been raised in a family where all electronic repairs were automatically undertaken by my 3 brothers of my father.

I feel my latest commission – the fantastical reality radio show – which I am creating along with two other artists and their agency, Mundane Appreciation – reflects a development on from the knitted speaker soundsystem. I am finding that my intentions behind using everyday sounds are much clearer and much more positive than in the knitted speakers piece. The audience is not left guessing; the playful framework of the radio show contextualises the everyday sounds in a way that the knitted speakers with their references to handicrafts, didn’t. I’ll play you now the sonic profile I made for myself as a personal introduction to the show:

The references to baking, to my garden, to craft etc. are all here, as in the knitted speakers piece, but I find this altogether less defensive than the earlier work.

I believe there is a way of writing, singing, dancing and making art about domestic space that asserts the power and history of woman’s contribution to that space, which articulates such assertions from an empowered, first-person point of view, and which acknowledges the historical fact of woman’s relationship to the home.

This is the approach I hope to take in my work with the domestic soundscape.

Pingback: The Domestic Soundscape » Blog Archive » Much loved.