The Domestic Soundscape making, listening, thinkingfelicityford@outlook.com

Bathing & Dressing parts 1 & 2

I mentioned a while back that there was potentially a commission to produce a soundtrack for a film in the pipeline. I am happy to announce that this project is going ahead and that throughout April 2012 – as well as working on this and designing this – I am creating a soundtrack for “Bathing & Dressing, Parts 1 & 2” for The British Film Institute and The Wellcome Library. These institutions are jointly funding this venture and you can watch part 1 here, and part 2 here.

It is an intimate film, harking from an exciting era when public health information films were in their infancy. In the early 1900s there was a left-wing, pacifist and Christian contingent in Bermondsey, who set about improving general awareness of health in the local populace by establishing better public facilities, and by utilising film to raise general awareness on the promotion of good health. The figure behind these historic developments seems to have been Dr Alfred Salter. Salter went into politics because he quickly realised when he moved to the borough that nothing he could do as a medical practitioner would be sufficient to counteract the lack of sanitation facilities, over-crowded toilets (sometimes 25 households shared a single WC) and other conditions of life challenging the health of the constituency. A committed group of amateur film-makers created many health-propaganda titles in Bermondsey, and these were then projected onto a canvas on the back of a bus in public spaces. There is more information about this here. The film for which I am creating a soundtrack was actually made in Shoreditch, in the Carnegie Model Infant Welfare Centre, established by George Frederick McCleary, but it seems to have grown out of a similar civic effort towards improving the welfare of Londoners by providing better education and sanitation.

I am fascinated by the culture of healthcare in this pre-NHS era, and have been giving much thought as to what a soundtrack might add to a film like Bathing & Dressing, which harks from such a specific context in history.

I believe strongly that sound design – like the design of a typeface or the design of a poster – is not only about creating an aesthetic, but about conveying information about the subject matter in hand. Therefore, I have spent a few days in the British Library familiarising myself sonically with the world in which the film was originally made. I’ve listened to oral histories from women who worked in maternity and midwifery during the 1930s when the film was made, and to domestic, home-recordings from the same era, to try and understand what sound-recording sounded like then. I’ve also listened to popular tunes from the era – particularly tunes written for young children; and I’ve listened to an account of Dr Salter, who was known to one of the interviewees whose oral history is on record at the library.

I have ordered some books to help me to better understand the world of the film, but there is so much information in sounds which cannot be conveyed in words that it felt important to explore as much as possible with my ears, rather than through written text. Afterall, my soundtrack will be heard and not read when it is completed.

The British Library Listening Service is an incredible resource. At the moment it is manned by just one person – the magnificent Ian Rawes of London Sound Survey fame – whose meticulously made and researched archive of actuality recordings from 1930s/40s London hosted on his own website has been invaluable in terms of helping me to “hear” the London of the 1930s.

I wrote to Ian with a list of record numbers. Much of what I wanted to hear was held in storage at Boston Spa, and some of it needed to be digitised for me to access it through the Listening Service. However Ian kindly sorted all this out for me, and then I was able to go to the british Library and sit in a carrel, filling my ears with accounts and sounds and taking notes with my pencil.

I discovered some wonderful 1920s/30s children’s songs, like Dicky Bird Hop, which Grace Fields recorded in the late 1920s. I love the whistling.

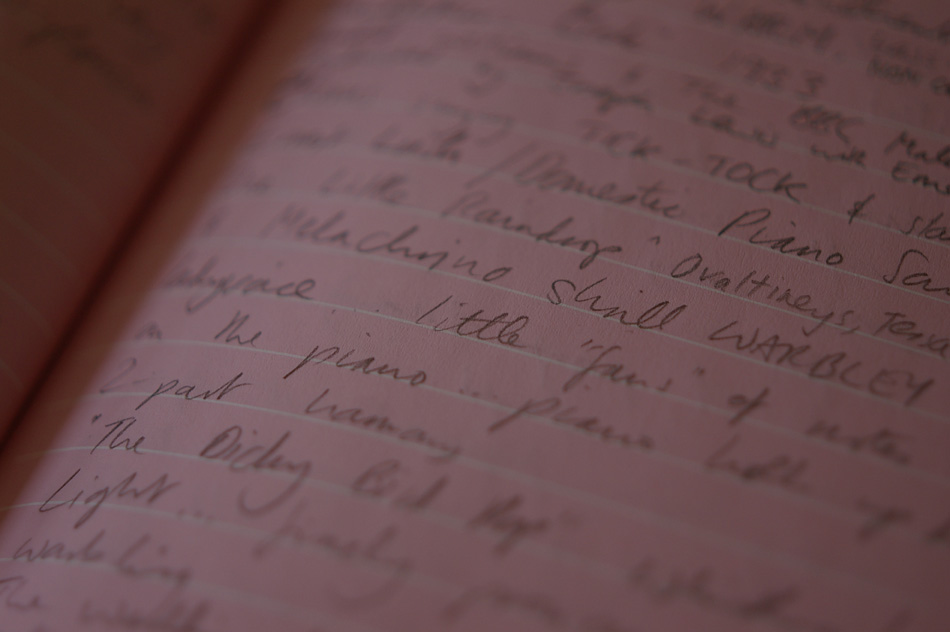

Perhaps more relevant in terms of my project, however, were the home-recordings of people playing the piano. There was a very interesting collection of domestic/local recordings which I presume was made before the 1960s, as they included a Methodist sermon on why hanging should be abolished. This collection features an amazing recording of a small religious gathering in someone’s home, including a hymn sung by a small gathering to the accompaniment of an upright piano. Here are my notes;

single mono microphone used;piano way louder than the singers

sounds of pages turning as music is played…

singing is unprofessional, it goes in surges and there is some talking and the notes aren’t all spot on… also the singers are some distance from the microphone BUT we sound like we’re in a living room… the piano is so determined under the singing… this is a living room recital. It sounds like a family singing because the voices feel between about 6 and 17… the mic can’t handle the high notes. Beautiful SE London accent saying a prayer in a proper, “posh” voice… the microphone has picked up on a clock in the room, people shuffle near the microphone… in The Lord’s Prayer, the voices drag along

I think there is so much information in that recording about people, place and time… it’s uncanny that you can hear the fact that it was made in a living room, but it would sound completely different if it had been recorded in a different kind of space, and the voices are so gorgeous as they are, with all the traces of class and religion which they articulate. When I learnt to play the piano, there were certain rules about how to “play well”, but what exactly does it mean to “play well?” And what if we were to think of piano-playing as a way of evoking or referencing eras in history, or specific social contexts? What if you want to play the piano to evoke the helpful, beat-keeping, driving determination of a pianist keeping a hymn-singing session in time, for example? Or if you want to play the piano in such a way as to evoke the informal use of that instrument for DIY home-entertainment for about 200 years of Western history?

Home performances are sentimental, and – as you might expect – the levels between voice and piano are not as well balanced or mastered as in a professional recording; also, the enunciation of words and expression of sentiment in the music have a sort of affected quality (which I also remember from playing the piano to my own relatives when I was young). Perhaps something of the size of one’s performance space – a living-room vs. a concert-hall – does something to confine the sounds of the piano-playing and singing, so that the expressiveness governing one’s performance (which would melt into reverb in a larger space) is somehow more live and present in an intimate setting? Certainly in the recording of the home-hymn-singing, I enjoyed these qualities in the sound as indicators of DIY culture and home-made entertainment.

In other recordings from that set I also loved hearing the disparity between the voices in the accidental recordings when the recorder was just left on, and the more deliberately-made recordings, in which people spoke with far more care and precision (something I’ve noticed about my own voice in radio work). There was something surprisingly moving to me about hearing the careful pronunciation of prayers in one section of the tape, vs. the far more relaxed and careless speech in other sections.

Perhaps the richest selection of home-recordings for my purposes is the K H Leech collection. I hunted down a large reel of magnetic tape from this, one side of which was full of informal domestic home-recordings, and the other side of which was full of parlour-room recitals on an upright piano. The recordings I heard were all made in the 1930s and 40s, and I enjoyed listening and noticing the distinctive sound and texture of a domestic piano session as opposed to a concert performance.

I particularly enjoyed hearing a recording in which Mrs Leech was clearly reluctant to participate and silently skulking in the background while Mr Leech (I think the recording was really his passion) and his daughter bantered about the price of sweets, and her use of her pocket money. What is amazing is that though the speech and words used are very different, their interactions with new recording technology are exactly the same as today; “is it on? is it recording? I can’t think of what to say” etc. are common finds in these home recordings, made I presume with a disc-cutter. Here are my notes;

“There are many ways of wasting a record… bad enough to just talk into the microphone…”

“Come on Pam, old bean!” (Pam is Mrs Leech)

“a bow of yellow” “lumpen sugar” “don’t be a silly chump” [expressions people wouldn’t use today!]

“the cutter is still cutting” [reference to recording medium]

so the record is being cut directly the sounds in the background are very far away… the acoustic is very hard to hear under the sounds of the medium… “haven’t got anything more to say”

It’s a Father and daughter playing with a record-recorder… (did I even hear a chicken in the background?) It sounds like its outside. Girl is eating a sweet… the medium is so crackly and poppy “long sticks and little balls” (she tries to remember the name of the sweet; she’s explaining what it is to her dad)

“I’ve only got a penny farthing left and I had threepence”

“It’s getting later and later each night” [Mrs Leech]

“I know I’m being recorded” [also Mrs Leech]

“say something quickly” [Mr Leech]

“something quickly” [Mrs Leech – churlishly]

There was also a Christmas Party recording from 1935 on this record, in which the participants stiffly express their gratitude for a wonderful day which included “blowing bubbles, playing ping-pong and doing all sorts of silly nonsense”. To me these details are very precious – and useful – as they help to detail a kind of atmosphere or context in which to make my own recordings. K H Leech’s own songs – sung and played it would seem by a huge range of accomplished friends – also made amazing listening, to me, and my notes will be useful for any such piano music which might/mightn’t end up in my soundtrack.

Rhythm pulls around/sentimental/very long notes… the piano is not entirely in tune and there are tiny modulations in the sound – I mean in the pitch (think Boards of Canada) causing it to waver. The crackles are interesting, too; they add a patina of age to the sound; a static. Are there ways I could emulate that sound?

recording scratches and pops off old record

try filtering and post-production on the piano track once I have recorded it

this is far too maudlin for my purposes… it sounds very miserable and over-sentimental

I could record the piano and then record that onto tape and play it back through my dictaphone to dirty the sound up a bit… also, could very slightly modulate the pitch to reflect the slight warpage of old record…

Mrs Hayes (singing) 1944

shrill and high register

proper HEAD voice; coming from the upper chest; and all the words sung as though marbles in moth; very soft and perfectly pronounced… tiny pops and cracklesOLD, snappy sounds… could fry onions and filter the sound massively… or a fire, massively filtered to create an OLD sound…

Characteristics of amateur piano recordings from 1930s/40s

hyper-expressive

pulling the tempo all around

quite earnest

sentimental

innocent

levels between Piano and Voice waiver and are not perfect throughout

many flourishes and broken chords (what is the Western Musical notation for a broken chord again? Is it a wavy line? * check*)

everything gorgeously enunciated

MONO recording – much less space than in a stereo recording*For the film soundtrack, the idea is not to create masses of EMOTION, but a device to give the footage sonic interest and to draw the viewer onwards. The sound is a reference to a time; it is a way of adding in extra information or meta-data to the footage. SOUND IS TEXT.*

I found it so useful to make these notes, to listen and write, to think through sound and hearing, and to make connections between ideas and recordings as I sat in my carrel at the British Library.

Finally – and perhaps most importantly for my purposes – the oral histories proved to be invaluable for helping to shape an idea in my mind of what the world of midwifery and post-natal care was like in the early part of the 20th century, in London. You can read whatever about midwifery, but to hear the emotion in women’s voices as they describe their work, their feelings about their work, and their personal histories conveys information which can’t be read. I was also very interested in listening to the women who went around collecting these histories in later decades – many of the recordings I heard were collected in the 1960s or 1990s, by women researching the history of women. The Voices of both interviewers and interviewees are incredibly rich and expressive, and I am utterly haunted by several oral histories which I listened to. I will refer to these women just by the years they were born in, as it is made very clear in the record details that anonymity must be preserved at all times. I wish you could hear their voices.

b. 1890

“I had a cloak… with a cape to it, brown, black hate, shiny straw with a red ribbon, and a pair of brown shoes”.

“The other children used to say to me “I’m not playing with you, you come out of the Union”. [Tendring Union]

“[My Foster Mother] wouldn’t go to a shop. I did the shopping. She never neighboured, she’d just speak, perhaps, but nobody ever went in… I don’t think she ever went in a shop. She’d go to Colchester and do a big shop on the Friday or Saturday. Mostly on a Friday, I remember, ’cause she used to get the joint. And she’d buy a picnic ham, I always remember that… we always had a hot tea. She kept a good table, I will say that. Good food, wholesome food, and meat puddings. And she was spotlessly clean. And she could make a shilling do when people spent two… on the corner – I can see it now – a sheet of foolscap and she’d put down every day what she’d spent, and on the Saturday she tabled it up. That was put on the fire and a fresh one put up for the next week”.

(This interviewee was fostered after staying in the Tendring Union; her foster mother had a son who was given very preferential treatment. She went on to teach at the local Methodist Sunday School. I listened to her interview to understand a bit about what life was like in the early part of the 1900s).

b. 1921

“bowling a hoop across Blackheath” “walking with a nursemaid” “boats on the river” “Mother played piano extremely well”

b. 1932 (my favourite interview of all), retired community midwife (never married, didn’t have children of her own)

“I have always had a great love for babes, and for any small thing, really”

“very open-minded when you decide to go into the community… a surprise to see how happy people could be with no money, and how people would make do”

“I remember my first birth… I was so afraid, but then pleasantly surprised to see a relaxed Mum with everything around her, and waiting for the great happy event to take place. It all went surprisingly well, so much so that I was very surprised to think that a little miracle could happen in this way… a baby could appear with no problems, and crying its little heart out. Yes, it was a great thrill, that visit”

(I was especially moved by this woman’s account of the role that faith played in her activities as a midwife, and especially the prayers that she made both for babies that were born healthy and happy, and at difficult births).

b. 1909

grew up in Poplar; old place. No proper bathroom. Toilet outside.

“rough living, food cooked outdoors, food was better” “rough life but we survived”

Not a big house. 2 rooms “for 8 of us”

Brother in Merchant Navy… AMAZING South London Accent… “very friendly – doors open, call in and out of neighbours’ houses” “Mum helped lady next door to deliver her baby”

“it’s a job to live today”

b. 1913

“born in Shadwell. Working class area. A lot of dockers”

“Mum was in charge of the garden; nobody dared tread on her patch”

“Father came from Warsaw, Poland, he was a machine embroiderer”

“Very long hours and very poorly paid; 8am/9am start work – Dad finished when all the babies were to bed, and after the kids were put to sleep, Mum went in to help and they worked together until 11pm”

“No running water at all. There was a yard with a tap in it; they washed in that yard”

b. 1909 also a midwife, also never married or had children of her own

“We kept mice at home, and I had fleece-lined blue bloomers. I used to put a mouse in there and it would come out at school. I’d get 4 pages of copy-writing for that”

“I had a temper, I didn’t like dusting”

“We [midwives] had an old Ford car; they used to call us “the flying storks””

“things were kept in a biscuit tin; this went in the oven right after it was turned off to sterilise”

“I don’t think they bothered much with “sterile””

List of things a pregnant woman should have ready for giving birth at home;

2 changes of bed linen

2 changed of bed attire

pieces of sheeting

a dozen napkins

3 vests

3 nighties

baby powder

soap

2 towels

plenty of newspapers

large milk jug

small basin/cup

sanitary towels

bucket/chamber pot

Midwife would bring:

large biscuit tin containing 12 squares white linen, packet of dressings, packet of cord ligatures, cotton wool swabs

rubber sheeting

newspaper and old sheeting, and big sheets of brown paper saved by the greengrocers for the midwives“any sheeting and old linen found at jumble sales, the midwives would boil up nice and clean and bring with”

“you got rid of the husband – he had to look after the other children, usually”

“I don’t think I ever prayed as hard as I did that night” [breach birth]

“got very close to the ladies”“First baby I delivered… Mum was a hockey player – Doctor said things like “push to the right wing” “score a goal””

b. 1918

“Dr Salter came to Bermondsey as a young doctor”

“you never had television, you never had radio, you had to go out on the street”

“Dr Salter had to attend women in appalling living conditions, he could see health couldn’t be improved while women lived like that… so he realised he had to be political. He sought to make Bermondsey a garden city”

“very irritated by “Women’s Issues””

I listened to so many accounts, and there are lovely details – like the brown paper that the greengrocers saved for the midwives, and the ingenious if not altogether sterile biscuit-tin-in-oven approach to “sterilising” dressings – which have stuck in my mind. The full result of mixing up all these voices, though, and these sounds, is that I have an idea now of how to go forward with this project.

I think that it will be necessary to have the voices of mums and healthworkers featured somewhere in my soundtrack for the film, because there is something about the quality of people discussing their memories informally which is extremely evocative. And although the mums and healthworkers who I find will obviously be of this era and not the original era of the film, so too will the audience. The sounds need to tell the story of those drafty, care-floorboarded, cramped interiors; of the lack of television and radio; and of the piano as the supreme home-entertainment system of the time… but the voices need to bring the warmth, the humanity and the experience of looking after a small infant to the soundtrack. They also need, I think, to bridge the gap between the THEN of the film and the NOW of now.

Who else would I ask for help with finding mums and healthworkers than my own Mum, and the woman who was my au pair when I was young? Thanks Bam and Catrine! …And thanks to the British Library for helping me to think and research through listening at your amazing archive.

Enamel basins, purchased especially for their evocative, sonic qualities.

Related

April 2, 2012 | Filed under Art projects, Listening, Making, Valuing Reality and tagged with British Library, Listening Service.

Tags: British Library, Listening Service

Copyright statement

You may transmit content found on this website (excluding my knitting patterns which are protected under International copyright law) under the following conditions:

- You always attribute my work to me, Felicity Ford, including a link back to this site

- You do not alter my work

- You do not use my work for commercial purposes

To discuss any other uses of my work, please contact me directly on the telephone number and email address provided at the top of this blog.

All the work shown here by Felicity Ford is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

From time to time I feature images, sounds or words on this blog which are not my own: in all such cases the original copyright owner is named. International copyright law requires that in order to republish their content, you must seek out their permission.

Thank you for respecting these terms and conditions.

KNITSONIK

To hear episodes of my podcast, KNITSONIK, please visit KNITSONIK.

Search Form

Archives

Powered by WordPress using the F8 Lite Theme

subscribe to posts or subscribe to comments

All content © 2025 by The Domestic Soundscape

Log in

9 Responses to Bathing & Dressing parts 1 & 2